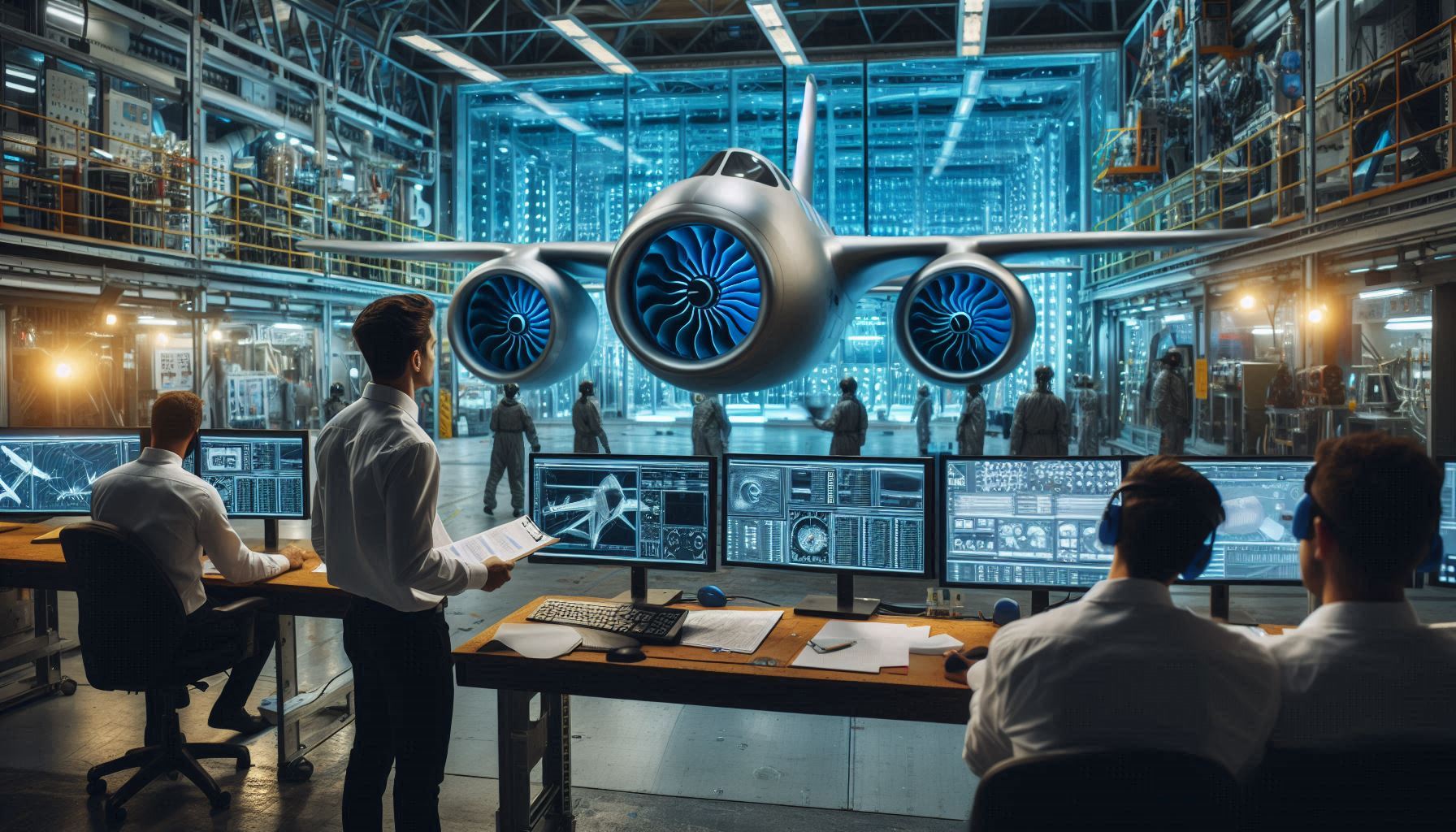

Canada’s aerospace sector has had a rare run of good news. Bombardier , long the country’s flagship aviation manufacturer , secured a new order from the Canadian Army this week, reinforcing its role as a trusted domestic supplier at a time when global defence spending is rising. Just days earlier, the company unveiled its newest long-range business jet, widely understood to be the Global 8000 series, a platform designed to push the boundaries of speed, efficiency, and ultra-long-haul performance.

For a company that has weathered a decade of turbulence ,from divestitures to restructuring to the sale of its commercial aircraft programs , these developments signal something important: Bombardier is not only stabilizing, but regaining ambition.

Yet momentum alone is not enough. If Canada wants to remain competitive in a world where aerospace innovation is accelerating, it must think beyond incremental upgrades and incremental contracts. It must think beyond subsonic flight. It must think beyond the limitations of relying on foreign propulsion systems.

Canada needs a homegrown engine capable of breaking the Mach 1 barrier , and it needs to build it through a coordinated public-private partnership that unites Bombardier, De Havilland, Pratt & Whitney Canada, the National Research Council, and the federal government.

This is not a moonshot. It is a strategic necessity.

Aerospace Leadership Requires Speed , Literally

For decades, Canada has been a respected but cautious aerospace nation. We build world-class business jets, turboprops, and engines. We excel in avionics, landing gear, and composite structures. We have a deep bench of suppliers and a workforce that is among the most skilled on the planet.

But we have never built a supersonic-capable engine.

That gap matters more today than at any point since the Cold War. Around the world, aerospace innovation is accelerating:

- The United States is investing heavily in hypersonic research.

- Europe is exploring hybrid-electric propulsion and high-speed regional mobility.

- Japan and South Korea are developing next-generation fighter engines.

- Private companies are reviving the dream of supersonic commercial travel.

If Canada wants to remain relevant , not just as a supplier, but as a leader , it must participate in the next frontier of propulsion.

A Mach 1+ engine is the gateway to that frontier.

Bombardier’s Opportunity, and Its Challenge

Bombardier’s new Global 8000-series jet is a technological achievement. It pushes the limits of subsonic speed, edging close to the sound barrier while offering unprecedented range. It positions the company as a premium manufacturer in a market dominated by Gulfstream and Dassault.

But the competitive landscape is shifting. The next generation of business aviation will not be defined by incremental improvements in cabin comfort or fuel efficiency. It will be defined by speed.

If a competitor , whether American, European, or even a private startup , introduces a reliable, economically viable supersonic business jet, the entire market will shift overnight. Bombardier cannot afford to be a spectator in that race.

A Canadian-built Mach 1+ engine would give Bombardier something no rival could match:

independence, differentiation, and a technological edge that could define the next 30 years of business aviation.

Why a Single Supersonic-Capable Engine Matters

The beauty of developing a Mach 1+ engine is not just the prestige of breaking the sound barrier. It is the platform versatility such an engine unlocks.

A well-designed, modular, high-performance engine could power:

1. Supersonic Business Jets

Bombardier could lead the next era of high-speed executive travel, just as it once led the regional jet revolution.

2. High-Speed Defence Drones

Canada’s defence sector is modernizing rapidly. A Mach-capable engine would enable:

- long-range surveillance drones

- rapid-response unmanned aircraft

- high-speed target drones for training

- autonomous strike platforms

This would reduce reliance on foreign suppliers and strengthen national security.

3. Advanced Trainers or Light Combat Aircraft

Canada has not built a military aircraft since the cancellation of the Avro Arrow. A modern, efficient, high-performance engine could revive domestic aerospace manufacturing in defence.

4. Next-Generation Regional Jets

De Havilland , another Canadian aerospace icon , could use a derated version of the engine for a new class of fast, fuel-efficient regional aircraft.

5. Experimental and Research Platforms

Universities, NRC labs, and private innovators could use the engine for:

- supersonic research

- aerodynamic testing

- propulsion innovation

- hybrid-propulsion experiments

A single engine family could support multiple industries, multiple companies, and multiple missions.

This is how aerospace ecosystems are built.

Public-Private Partnership: The Only Path Forward

Developing a Mach-capable engine is expensive. No single company , not even Bombardier or Pratt & Whitney Canada , would take on the full cost alone. But a public-private partnership changes the equation.

Canada has done this before:

- The Canadarm

- The CF-18 modernization program

- Satellite and space robotics

- National research superclusters

A propulsion initiative would follow the same model:

Government Provides:

- Funding

- Regulatory support

- Defence procurement commitments

- Research infrastructure

- Long-term industrial strategy

Industry Provides:

- Engineering expertise

- Manufacturing capability

- Testing facilities

- Commercialization pathways

- Export potential

This is not corporate welfare. It is strategic nation-building.

Why Now? Timing Is Everything

Three forces make this the perfect moment for Canada to act.

1. Bombardier’s Resurgence

The company is leaner, more focused, and more ambitious than it has been in years. It has the engineering talent and the market presence to lead a high-speed aviation program.

2. Global Defence Realignment

NATO allies are rearming. High-speed drones, advanced trainers, and rapid-response aircraft are in demand. Canada can supply these , if it has the propulsion technology.

3. The Need for Domestic Capability

The pandemic exposed the fragility of global supply chains. Relying on foreign propulsion systems for critical defence or commercial programs is a strategic vulnerability.

A Canadian Mach-1+ engine would be a national asset.

Economic Impact: A New Industrial Engine for Canada

A propulsion program of this scale would create:

- thousands of high-skilled engineering jobs

- new manufacturing facilities

- export opportunities

- research partnerships with universities

- spin-off technologies in materials, AI, and robotics

It would also strengthen Canada’s position in global aerospace supply chains, ensuring that the country remains a top-tier aviation nation.

The economic multiplier effect would be enormous. Aerospace jobs are among the highest-paying in the country, and every dollar invested generates multiple dollars in economic activity.

The Strategic Case for Speed

Speed is not just a technical metric. It is a strategic advantage.

In business aviation:

Executives will pay a premium for faster travel. A Mach-capable Bombardier jet would dominate the ultra-long-range market.

In defence:

High-speed drones and aircraft reduce response times, improve survivability, and expand mission profiles.

In research:

Supersonic platforms accelerate innovation across materials science, aerodynamics, and propulsion.

In national prestige:

A country that builds a Mach-capable engine signals to the world that it is a serious aerospace power.

Canada has the talent. It has the companies. It has the history. What it needs is the ambition.

Learning from the Avro Arrow , Without Repeating Its Fate

The Avro Arrow remains a symbol of what Canada could have been , and what it could still become. The lesson of the Arrow is not that ambition is dangerous. The lesson is that ambition must be supported, funded, and protected.

A Mach-1+ engine program would be a modern, realistic successor to the Arrow’s spirit. It would not require building a fighter jet from scratch. It would require building the one component that unlocks everything else: propulsion.

If Canada builds the engine, the aircraft will follow.

A Vision for the Next 20 Years

Imagine a Canada where:

- Bombardier launches the world’s first Canadian-built supersonic business jet.

- De Havilland introduces a new generation of fast, efficient regional aircraft.

- The Canadian Armed Forces deploy high-speed drones powered by domestic engines.

- Universities and research labs test new aerodynamic concepts using Canadian propulsion.

- A new aerospace corridor emerges, stretching from Montreal to Toronto to Calgary.

This is not fantasy. It is a strategic roadmap.

Conclusion: Canada Must Choose Ambition

Bombardier’s new military order and the launch of its latest jet are encouraging signs. They show a company , and a country , that still has aerospace in its DNA. But to remain competitive, Canada must look beyond incremental progress.

A Canadian-built Mach-1+ engine is the key to unlocking the next era of aviation leadership. It would benefit Bombardier, De Havilland, Pratt & Whitney Canada, the defence sector, and the broader economy. It would create jobs, strengthen national security, and position Canada as a global innovator.

Most importantly, it would give Canada something it has not had since the days of the Avro Arrow:

a bold, unifying aerospace project worthy of a nation with world-class talent and world-class ambition.

The moment is here. The opportunity is real. The only question is whether Canada will seize it.